When I first saw Let’s Go Together, the powerful painting by Terrilynn Dubreuil (the feature image for this post), I was immediately struck by both its tenderness and raw and loose mark-making. The piece is part of a deeply moving series that Terrilynn created after her mother’s passing — work that explores love, loss, and the bond between mother and daughter.

I invited Terrilynn to share these paintings and the story behind them because I know how many of us turn to art in times of grief. Her reflections on how painting helped her to process emotion — and how it transformed her artistic voice — will resonate with anyone who’s ever picked up a pastel (or a brush) to make sense of what words sometimes can’t express.

About Terrilynn Dubreuil

An internationally recognised artist, curator, and mentor, Terrilynn Dubreuil holds a BFA and has taught for over 35 years in diverse settings — from international events like Pastel Live, the Plein Air Convention & Expo, and Mastrius to her own Patreon and classes with pastel and watercolour societies worldwide. A Master Circle member of IAPS and Signature Member of both the Pastel Society of America and Pastel Society of Maine (where she also serves as Vice President), Terrilynn’s award-winning paintings balance realism with emotional intensity. You can explore more of her work here.

And now, here’s Terrllynn Dubreuil!

*****

A Mother, a Daughter, and Art

Mothers and daughters don’t always have an easy relationship. Between my Mother and me there were certain topics we simply had to avoid if we were to enjoy our times together. Like a piece of sanded pastel paper, there was a side that brought joy and the other that was best left untouched.

The functional side for us was Art. Art was always a joy to discuss. We were both teachers, and we shared so much about the experience of creating. She was a watercolourist; I was drawn to soft pastels.

We had an unusual relationship, I realise. She was in my life so much longer than many others have their mothers — she was nearly 98 when she passed.

The Seeds of an Artist

Looking back, I was a preteen when she began her own pursuit in art. She filled the house with books on Art History, North Light instructional guides, art magazines — and those became my first art teachers. We had no formal art programme during my school years, so I’d spend hours poring over those pages, absorbing colour, detail, and the stories of the masters. At the library, I’d head straight to the Art section, pull out the largest books I could find, and lose myself in the “plates” of great paintings.

As I said, I had no formal art classes until high school, and even then only for six months — when my Mother herself became the temporary art teacher. She had pushed for the position and brought fundamentals and self-expression to our school, even if just for that short time.

A few years later, during my junior year at university, I finally decided to major in Fine Arts. After that, the minutiae of life left us little time to share our art, even as we both continued to teach and create. In her later years, when she could no longer paint, we would look at artwork together, critique and discuss. She was proud of my growing success with pastels.

The ‘Reflections’ Series

After she died, I felt driven to express the complexity of my emotions by painting her in a series of works I called Reflections. As her body crumbled, her mind remained quick and alert. To me, the most impactful painting is Her Hands.

I was stunned when it received First Place in the 2023 IAPS exhibition. My quick, rocketing elation plummeted the moment I caught myself thinking, “I need to tell Mom!” — and realised she was no longer here to tell.

In the series, I used energetic and seemingly chaotic marks to portray the sense of fraying reality — the tattering of a person’s being as they transition from this life to the next.

Painting from Memory and Emotion

I’ve always been fascinated by painting people — not merely their likeness but something deeper: their emotions, their personality, their movement, their moment in time.

After I lost my mother, all I had were photographs, many taken clandestinely during her later years so I could hold onto our moments together. At first, these photos were private mementos. But then I began painting from them, focusing on her hands, her face, her relationship with her beloved cat. I intuitively found myself using her favourite colours, the chair she spent her final years in, and the frayed marks that, to me, suggested a spiritual transition between worlds.

I began each piece by laying out shapes and values from the photos, then set the photos aside and painted intuitively from memory. Something inside guided my hand — an unrestrained, almost urgent need to create. That freedom helped me process the loss, the distance, and the complex imperfection of the woman who was my mother.

The Story in Her Hands

Her hands were loving, caring, always creating — so I exaggerated them in the painting. She painted award-winning watercolours with those hands. She cooked, cleaned, and cared for others. She taught art to children, university students, and private pupils for years. She looked after her family, her pets, her Hospice patients, her relatives — those hands did amazing things in her 97 years.

At sixteen, she was a draftsman at Bath Iron Works in Maine, drawing ship hulls during World War II. She had been on her way to becoming the youngest person to earn a pilot’s licence when tragedy struck — her stepmother burned down the family home, destroying everything. Instead of flying lessons, she went to work in the shipyard, drawing blueprints for the hulls of the battleships. Quite extraordinary for a young woman of her time.

During the pandemic, her hands were thin-skinned, the tendons visible, yet still capable of holding playing cards and finishing crosswords daily. They were miraculous.

Painting Through Grief

My mother had endured a difficult childhood, which made her seek structure and order in everything. Her hair was her “crowning glory.” Her clothing, manners, and home were always impeccable — not out of vanity, but as a way to maintain her own sense of solidity and security. People loved her — her family, her friends, her students, her community.

In her final years, as her body crumbled, she could no longer keep up her carefully groomed appearance or the neatness of her home. I found myself oddly fascinated by that slow dilapidation and wanted to express this in my painting.

I would never have shown her these paintings — oh, she would have been mortified — but as she was gone, I could express what I felt in my loss. That honesty, that release, was deeply healing.

A Shift in My Work

Looking back at earlier portraits, I can see my style was more precise and controlled. Expressive, yes, but contained. I painted my granddaughter — my muse — many times, and also friends or their children, with careful accuracy, trying to capture their features. I even once had fun creating a portrait of Danny DeVito for my daughter’s birthday!

But after painting my mother’s series, everything changed. My work became looser, more expressive, and more personal. I paint now for myself, not for others’ approval. I experiment more boldly with techniques and materials, finding joy in the act of creation itself.

New Directions

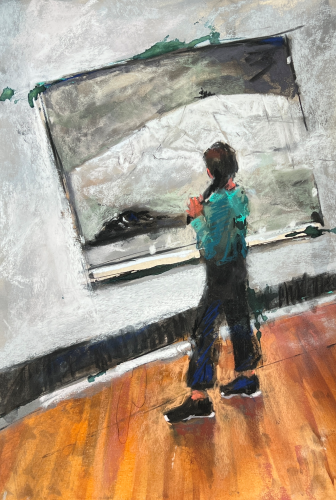

Some of my recent pieces have taken on subtle social commentary. Unsettled, for example, shows a girl stopping to look at an Andrew Wyeth painting in a gallery. The tipped horizon and shredded surroundings suggest the precarious world young people inhabit today. She stops in her tracks captured by the painting, holding her braid as if it were a rope of security. Her feet point forward to the future but her mind is trapped by the evasive meaning of the Wyeth painting.

This work has received little response — yet that no longer matters to me. I painted it to express my feelings. And isn’t that, after all, what art is for?

Looking Back, Looking Forward

I find myself returning to my early artistic heroes — Käthe Kollwitz, Francisco Goya, Honoré Daumier — and their powerful portrayals of humanity. They remind me of what truly moves me to paint.

In my own “serious” work, I now ask: Why am I painting this? What do I want to express? How can I create emotional statements that reach others, that communicate something universally felt?

This isn’t always an easy pursuit — but it’s the one that matters most to me now.

At the foundation of it all lies with my Mother’s influence: her teaching, her example, and the final impetus of her passing, which propelled me to create art that helps me process my own powerful and convoluted emotions.

Is that not one of the greatest purposes of creating art?

~~~~~

Such a moving story — and what a beautiful example of how art can help us navigate grief and find meaning in the process. I’m grateful to Terrilynn for trusting us with such a personal journey and for reminding us that even in loss, creativity can offer connection and healing.

I’d love to hear what resonated most with you. Have you ever painted (or created) through loss or emotion? How did it shape your art?

Please share your thoughts and reflections in the comments — both Terrilynn and I would love to read them.

Until next time,

~ Gail

14 thoughts on “Terrilynn Dubreuil – The Power of Art to Process Loss”

It is very touching. It lets me cry. I miss my mom too, but I don’t know how to draw like bread Terrilynn. Thanks for her great sharing.

Thank you for sharing your response to Terrilynn’s post. Remember, it’s not so much about the outcome but rather, it’s the process itself that helps with healing Yu-wei. I hope you will try to let art-making help your with your sad feelings for your Mum.

I loved this, thank you. I am going through my own journey at the moment with my Mother who is 93. She lives with me and I am her full time Carer. Our relationship is very complex and not necessarily easy. But as I deal with her frail body I have a great desire to capture its beauty (and I truly believe this is the way to describe it – an incredibly fragile beauty) in pastel. However, the emotional and physical impact of our lives has stopped me from painting altogether and it has now been many months since I have picked up a pastel and felt that it belonged in my hand. Perhaps your exquisite paintings will help me move forward. Regardless, I very much appreciate your post and the opportunity to see your work. ❤️

Ohhhh Kerrie, I feel your anguish. And I love that you too see the beauty in her frail body. I hope this will inspire you to put pastel to paper to help with your emotions and also capture something of your Mum and your relationship. This post by Terrilynn seems very timely….

A very moving piece.

Lost my mum and dad 15 yrs ago and I feel the loss as much now as I did then.

I struggled with faith until their passing but strangely in the years since I have taken up art which helped me reconnect with my spiritual side, this has given me some comfort

Ahhhh Roy, thank you for sharing your own journey and feelings of continued loss. You bring up another benefit of art-making – connection and spirituality. Thank you!

Oh, these pastels are all so wonderfull. Look at Penny, how alive she is, where children painted fro a poto by ther granparents often are flat and lifeless. The paintings of her mother are so moving and beautifull. Thank you Terrilyn for sharing it.

I am not very good at pastel, but love to do it from time to time and follow courses, Terrilyns at Artefacto school, Stephie Clark, you Gail in your blogs and enjoy it immensily.

So, when my little cat, Witje, unexpectedly fell seriously ill and died in the hands of me and my daughter when we tried to give her some water, while she would have preferred to die under the closet. We were terribly upset and I drew her body dead on the ground, before we buried her. We gave her some large ice-age stones on her grave, a pot with flowers and an automatic candle that starts at 5 pm.

Ohhhh Nicolein, thank you for sharing your own journey of loss and regret too. I’m glad you honoured your wee cat by painting her after she died.

This is a lovely blog and Terrilynn’s article is beautiful, moving and inspirational.

Thank you both!

Robert

That’s so great to hear Robert!!

Gail, thank you for your blog and website. I look forward to each new entry for the learning and inspiration they provide. Terrilynn’s article was particularly meaningful and helpful. Both my parents died decades ago. I have painted them several times, but will now approach some of the same paintings a second time with a deeper understanding of why I am doing it. Thanks!

Thank you Brooke for your wonderful words of appreciation – for the website and blog. And I’m delighted to hear that Terrilynn’s guest post has inspired you to look more deeply at your own painting responses to your parents’ deaths.

What a beautiful article written by TerryLynn. So honest in her assessment of mother/daughter relationship but then how much we worship our moms and want to honor them. l appreciated how TerryLynn shared how her style has changed as her relationship with her own feelings changed. I think that is the real takeaway for me, is we need to portray our feelings and our love of pastel in our work. Another amazing guest artist. Thank you Gail

Thanks for sharing your main (and fantastic!) takeaway from Terrilynn’s article Christine. I too think it is wonderful to see Terrilynn’s growth in style and depth through this painting/healing process.